The Covid-19 pandemic has had a far-reaching impact on the already poor perception of the importance of early health care access in rural Malawi.

An AfricaBrief investigation has revealed that some pregnant women as well as patients suffering from other ailments are avoiding getting medical treatment from established health centres across the country.

There is an unfounded fear that visits to the health facilities have resulted in Covid-19 infections and eventual death.

At the peak of the pandemic, between June and October 2020 for example, one district in the country recorded a 50 percent drop of patients that patronized health centres in the area in a month.

This investigation has revealed that some are dying of treatable diseases at home because, either their guardians refused to take them to health centres, or they had simply decided to stay home or seek treatment elsewhere, other than at health centres.

But why? Let’s unravel a complex tangle of reasons, with the emergence of Covid 19 at its core.

What’s driving the fear to go to hospitals?

Our journey to unravel the reasons behind these drops in hospital attendance during the coronavirus pandemic in Malawi started in Mzimba, a district in the northern region of the country.

In Katiyo Village, Traditional Authority (TA) Mzikubola to be more specific.

“Before the pandemic, I used to go to the hospital to access health services whenever I fell sick, but then I stopped after rumours started making rounds that medical workers were at these facilities deliberately infecting patients with Coronavirus,” said Maria Mwase, one of the locals in Katiyo Village.

“We heard that just after a few days after being infected, these people would die in their homes, with some becoming very sick after the injection.”

Later, we found out that Maria’s fears exemplified those expressed by many expecting mothers and others who are suffering from other ailments in Malawi; many have chosen not to access and utilize health services at the country’s health facilities since the country recorded its first case on April 2, 2020.

Maria, who was seven months pregnant at the time of the interview, said, “ We also heard that these medical workers had stopped giving patients the infected syringes because people had apparently uncovered their tricks, and we heard that they were then instead of giving patients contaminated tablets to take, which was another trick for them, too.”

Maria said, as an alternative, she and other fellow pregnant women in her area were then relying on Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs), whose work in Malawi has been mired in controversy because the low-skilled TBAs were said to be unable to identify obstetric emergency cases early enough. TBAs are also banned in the country.

Maria seemed to be aware that she was putting her life and that of her unborn baby at risk.

“The problem that I started facing was that these traditional birth attendants didn’t have the proper equipment for maternity checkups as compared to nurses who used to provide us with every necessary support, including providing us with medicine after every checkup. Right now, we are experiencing many problems,” said Maria.

From Mzimba, we headed to Mzuzu, fondly called the Green City due to its beautiful scenery.

Here we talked to two pregnant women we found at St John's Hospital: Fryness Kilembe from the Chigwere area and Isabel Nkhoma from Chingamo; both places are within the city.

They had come to the health facilities for their pregnancy checkups for the first time in several months.

“We had completely stopped coming to the hospital because of fear of reports that once you visit the hospital you would be diagnosed with Covid 19, be forced to isolate, and then die mysteriously,” said Fryness.

“We heard these rumours that doctors were also telling everyone who went to the hospital that they were infected with Covid 19, even if those people were suffering from other diseases like Asthma, high blood pressure, or TB.”

Isabel, who at that time was listening attentively to what her friend was saying, then chipped in.

“We also heard that whenever pregnant women like us went to the hospital, they would not receive proper care because doctors were busy with Covid 19 patients in the hospitals,” she said.

Isabel said they had gone to the hospital on that day not just to seek medical help, but also “because we wanted to prove what people were saying about Covid 19 in hospitals”.

“We have seen that it’s not true. What people were saying out there is not true at all: they are all lies,” she further explained.

The two women said, just like other pregnant women in their neighbourhoods, they used to go to traditional birth attendants for alternative help but said they were being asked to procure drugs locally from costly pharmacies.

From Mzuzu, we took the Lake Shore Road, heading to Balaka district in the southern region of the country, where we met Sylvia Bamusi, one of the few pregnant women who had come for their checkups at the hospital on that day.

Sylvia reinforced what the women in Mzuzu had told us about their experiences with Covid 19 and hospital attendance.

“The biggest problem we are having here is that most patients are afraid of contracting the virus while getting treatment for other diseases at the hospital,” said Sylvia.

“Right now, as we speak, some of my fellow patients have escaped from the wards, fearing getting infected. I must be honest with you: I’m not even comfortable to be here.”

Then from Balaka, we headed to Blantyre District Health Office. Before the pandemic, hospitals in the district would get an average of 120, 000 patients in a month, according to data sourced from the DHO.

At Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital (QECH), one of the busiest referral health facilities in the country, we met 25-year-old Mercy Bwanawo, who had come for her pregnancy checkup in months, after shunning the health facility in light of the pandemic.

“When Covid-19 had just started, I was afraid to go to the hospital because people would say that whoever goes to the hospital would not come back alive, and so, since I didn’t have enough knowledge about the new virus, I decided to stay home fearing that I would not come back alive from the hospital,” said Mercy.

“At one time, I had some fever, but I would just drink water and some Panadol which I bought at a local grocery till I got better. But of course, it took a long time for me to get better.”

Mercy, a mother of two, said her husband was also contributing in instilling fear in her mind, as he would reportedly tell her not to ever visit the hospital because she would die from the virus, “and the children will be orphaned”.

Son dies because family could not take him to hospital in Kasungu

Fears that medical workers in the country’s health centres were deliberately infecting patients with Covid 19 were nearly everywhere in Malawi, in both rural and urban areas.

For example, in Kasungu district, which is in the central region of the country, a father refused to take to the hospital his 6-year-old boy who was struggling to breathe. The child died a few days later, apparently from pneumonia.

Journalist Harold Kangoli, who witnessed this sad incident, said he told the man, Lifton Kamwana, who happened to be his friend, to seriously consider taking the sick boy to the St. Andrews hospital, the nearest hospital, at the journalist’s expense.

“He shook his head in disagreement and said he couldn’t do that because the doctors nowadays are after money and would ‘turn’ any disease into Covid 19. He claimed that the medical workers were even injecting poison into people so that they should get more allowances,” said Harold.

“I was shocked by his statement, and when I told him that he was making a wrong decision for the innocent boy, he said, ‘If it's dying, let my boy die.’”

Harold said his efforts to convince other members of Lifton’s family on the matter proved futile, as they all told him that no one in their area was going to the hospital for treatment when they fell sick.

Mark of the Beast

While some believed the unfounded claims that health workers at health centres in Malawi would infect them with coronavirus, others were worried that the Covid-19 vaccine would brand people with the “mark of the beast”, as described in the New Testament’s Book of Revelation.

For example, in July 2021 a family of four in Lilongwe isolated itself in a house for two months because they believed the Covid-19 pandemic was a sign of the end of time.

After a while, the community in which they live suspected the isolation was for witchcraft reasons and begun to attack them but the police rescued the family.

Deputy PRO for Lilongwe Police Station, Sergeant Foster Benjamin said Dismess, 50, his wife Enele, 50, and their two daughters aged 16 and 18, respectively, had isolated themselves for two months without eating anything save for drinking warm water.

“We thought everything about the pandemic, including masks and vaccines, was part of the mark of the beast – a cryptic mark in Revelation which indicates allegiance to Satan,” said Dismess.

“This is because of the way governments and other organizations worldwide are enforcing the rules on the pandemic.”

Crunching the Numbers: How Covid-19 Caused the Drop in Hospital Attendance

Across all three regions of the country, COVID-19 has significantly impacted access to and utilization of health services for pregnant women and other patients in Malawi.

The drop in hospital attendance varied from one place to another, but it looks like Blantyre district, in the southern region of the country, bore the brunt of this “hospital boycott”, which was evident during the second wave of the pandemic in Malawi, from June 2020 to November 2020.

For example, in May 2020 the District Health Office in Blantyre recorded 107,587 patients, but come June 2020, the DHO recorded only 58,285 patients in all its facilities.

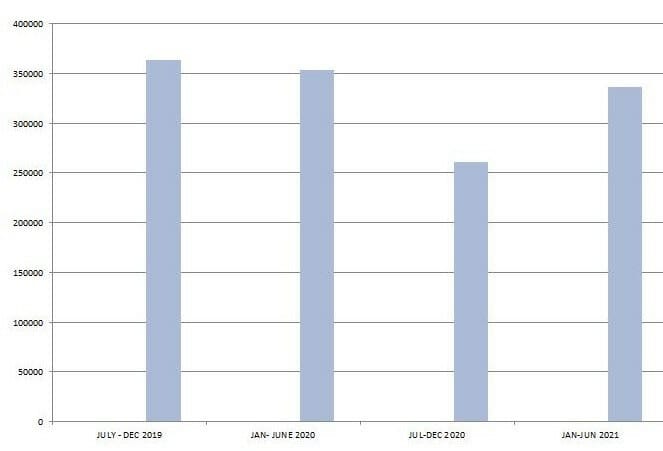

As the accompanying diagram shows, the drastic drop continued, as more and more people, especially pregnant women, continued with the hospital boycotts in light of the pandemic.

Elidah Vutula, the Safe Motherhood Coordinator for Blantyre DHO, said these figures are stark—in terms of not just the potential impact on health outcomes for pregnant women—but even worse when looking at access to health services in general.

“We usually tell all pregnant women to go for antenatal services as early as three months of their pregnancy, but then as of now our figures have drastically dropped because of the Covid-19 issues,” said Elidah.

“For example, a mother died because she was afraid to come to the hospital: she had delivered at home. She was afraid to come to the hospital because of Covid 19 issues, as she was allegedly afraid to be injected with the Covid 19 vaccine.”

Elidah said they were holding meetings with religious leaders and “we hope that religious leaders are going to assist us to empower the community with the right messages on the pandemic”.

On his part, Jimmy Banda, Public Relations Officer for St John's of God Hospital in Mzuzu said the occurrence of the Covid-19 pandemic saw a reduction in the turnout of patients visiting the hospital for medical support, compared to the pre-Covid 19 period.

“The hospital registered a decline in the prenatal patients from 978 before the pandemic hit the country to 754 in the six months from July to December when the pandemic hit the nation in 2020.”

Banda said, just like in other parts of the country, misinformation was the major cause of the “boycotts”.

“The hospital is being regarded as the hub where people are contracting the virus, and anyone visiting the hospital is reportedly being forced to be diagnosed with the Covid-19. In the prenatal section, the hospital registered 120 patients in May 2020, and in May 2021, the hospital registered 114 clients, which is a continuous decline in the patients' turnout.

Meanwhile, Ellings Nyirenda, Mzimba District Hospital Public Relations Officer, said the trend has been the same at the health centre, with people fearing that they would be tested for Covid 19 even they had come for other health problems.

However, he said it was encouraging that a good number of people in the district have started realizing that the myths are just retrogressive, as no one has turned into a zombie for example after taking the Covid 19 vaccine.

Balaka DHO- Mercy Nyirenda, too, said the “hospital boycott” was rampant because people had the wrong information.

“They were being misinformed; for example, they were rumours that once you take your child to the Under-Five clinic, the child will automatically get the Covid 19 vaccine.”

Just like most health facilities in the country, Bwaila Hospital, “the mother hospital” within the city of Lilongwe had a fair share of the problem.

Normally the facility received an average of 1,200 new pregnant women per month for antenatal services, then when the Covid 19 pandemic was at the peak in January and February 2021, the number of attendees dropped to an average of around 800 to 900 in a month.

What is the Ministry of Health Saying About All This?

Ministry of Health Spokesperson, Adrian Chikumbe, said the ministry observed that COVID-19 and the restrictions put in place to manage the spread of the pandemic had negatively affected people’s decisions on whether to go to health facilities.

“Uptake of maternal and newborn health services were slightly affected by Covid 19 during the first wave and the second wave, and as some pregnant women were afraid of seeking ANC (Antenatal Screening), labour and delivery as well as postnatal care services, fearing to contract the infection from fellow patients or health care workers,” said Chikumbe.

Antenatal Screening comprises several crucial tests that pregnant women have to take during their pregnancy. These tests include blood tests, hemograms, and urine routines.

However, Chikumbe said with the third wave of Covid 19, most facilities reported no significant changes in numbers of women seeking ANC, and other services, although few health facilities continued to experience low turn up.

“Already, postnatal care visits in Malawi, after 1 week and 6 weeks, are already low in Malawi, so this was replicated. The reason is that mothers always see no need for going back to hospitals for checkups when they don't see any need,” said Chikumbe.

Chikumbe said although the numbers of pregnant women going for ANC were increasing during the third wave, there were some notable observations.

“For example, many antenatal women in the waiting homes or shelters were being infected by Covid 19. This led to having newly-born babies that were born with Covid 19, and some pregnant mothers with severe symptoms were dying from the virus,” said Chikumbe.

In July 2021, Mangochi District Hospital had a case of a two-week baby that was diagnosed with coronavirus. The baby, born from an already positive mother at Koche Community Hospital in the district, had chest in-drawings, fever, and cough. Although it was put on oxygen and isolation, the baby died two days later.

To deal with the problems of myths around the pandemic, Chikumbe said his ministry and its partners have embarked on resource mobilization of Personal Protective Equipment (PPEs), for example, face masks, gowns, Googlers, hand sanitizers that were distributed to all health facilities.

He said due to the misinformation flying around the pandemic, some women were attending ANC, labour, and delivery care services at traditional attendants for fear of Covid 19.

“The TBAs were happy to take care of these pregnant women, despite the policy which bars them from providing such services.”

The hospital boycott has also caught the attention of the Nurses and Midwives Council of Malawi, according to the Acting Registrar, Judith Chirembo.

“In the first place, the pre-Covid period had our hospital wards overwhelmed with admissions in all departments. Most district hospitals and central hospitals filled their bed capacities. However, after Covid-19 was confirmed in Malawi and screening of people and patients coming to the hospitals was intensified, the number of patients accessing care decreased,” said Chirembo.

Chirembo said although the council did not have handy data for this account, this was noticed during their routine inspections of the health facilities.

“Many wards in the hospitals were half empty most of the days.”

She said the decrease was mostly noticed in October 2020 through June 2021 when NMCM conducted the inspections jointly with their sister regulatory body, the Medical Council of Malawi.

“Randomly, the reasons given by health facilities that registered a reduction in in-patient admissions as well as outpatient attendance during this period was that there were a lot of myths concerning Covid-19. The awareness messages were not adequately addressing the believes or misconceptions people had. As such people chose to not visit the hospitals for care when sick.”

However, Chirembo said the third wave of this viral infection has “made most people understand and accept that Covid is real”.

“Visiting most hospitals now one will observe that patients are accessing care in these hospitals and most wards are filling up,” said Chirembo.

Health Rights Body Weighs In

The Executive Director of Malawi Health Equity Network, a health rights body in Malawi, George Jobe, said myths, misinformation, and beliefs have affected the health-seeking behaviors of some Malawians just because of Covid 19, especially among expecting mothers.

He said it is a health risk when someone is not feeling well and opts not to go to a health facility.

“What we think and have been seeing is that the communication that happens on this pandemic must be a combination of different strategies, including informal or traditional media whereby community leaders must be involved to also not only be recipients of information of Covid 19, vaccines, about the need for healthy seeking behaviours in time but also agents of communication,” said Jobe.

What do Communication Experts Think about the Problem?

Earlier this year, Focus Maganga, a Malawian health communication specialist based at Malawi University of Business and Applied Sciences, made a presentation on behalf of his other four colleagues during the Health SBCC Conference in Malawi.

In their presentation, they maintained that Effective Risk Communication and Community Engagement (RCCE) was critical for the successful implementation of all emergency programming, including COVID-19.

We asked Focus to explain how he rated the use of RCCE in Malawi in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, considering that a large section of the country is still hesitant on taking vaccines and still believes in myths around the pandemic.

He said in any public health emergency, there are set health emergency readiness and response activities that the World Health Organization prescribes that should happen to swiftly and effectively contain the emergency.

“RCCE is one of those pillars and it is, through this pillar, that myths, misconceptions, and risk perceptions about the emergency are addressed. Through our study and related studies conducted in the country, there is evidence people now know about the disease and other basic information about the pandemic. That means we did well in this area,” said Maganga.

But he said it appears government and professionals didn’t have time to plan the country’s response and engage all important stakeholders before the disease penetrated the country and started being transmitted from one person to the other in the communities.

“That is why the government needs to engage all important stakeholders including experts and local leaders and come up with RCCE guidelines embedded in a national strategy. That will also inform our internal risk communication systems for sharing information and opinions both internally and with partners in the public health emergency responses. It can also help handle better future epidemics and other emergencies.”

Focus also said that “there is a need to track and correct wrong information about the pandemic”.

“It is called social listening and includes tracking information related to the epidemic that people are sharing on social media and in their offline social circles intending to provide real-time accurate information on any misrepresentation of truths.”

Maganga said the research work on RCCE in Malawi was co-authored by Dr Flemmings Ngwira, Goodwin Gondwe, Bester Nyangwa and Tobias Kunkumbira.

What has been happening in Malawi on the health front during the pandemic has immediate consequences on the health of women, including mothers, and their children, but also on communities at large.

Since the outbreak of the pandemic in the country, uptake of the vaccine in Malawi has been low and at one time health authorities incinerated 19,610 expired doses of the AstraZeneca coronavirus vaccine because people were-and still are-hesitant to get vaccinated.

As of 26 September 2021, at least 489,199 people in Malawi were fully vaccinated, but the government intends to vaccinate at least 11 million Malawians by December 2022.

Clearly, COVID-19 risks rolling back important gains in health development in the country, if nothing meaningful is done.

*This story was produced with support from Highway Africa and PSA Alliance.