By Kunle Adebajo and Murtala Abdullahi

Photography by Kunle Adebajo and Murtala Abdullahi

Data analysis by Mansi Muhammed and Yuxi Wang

Visualizations by Yuxi Wang and Jillian Dudziak

CCIJ Editorial and Design Team: Lydia Namubiru, Yaffa Fredrick, Scott Lewis, Jillian Dudziak

NIGERIA: A bare-chested old man lies in the emergency room of a government hospital in northeast Nigeria. An intravenous line sticks out from his right arm and an arrow from his left shoulder. A second arrow, with the tip now detached from its shaft, rests on a bedside table some feet away. About a third of the man’s left arm is dressed in blood-stained gauze. The blood stains are also visible on his white trousers and his unbuttoned navy blue jacket. Within a few hours, Usman Alhaji Mikaila has gone from working on a rice farm to fighting for his life.

The previous day, at a farm in Nguru, Yobe state, where Mikaila was the foreman, workers were husking recently harvested rice when a herd of cattle started grazing on the same field. Normally, Mikaila said, the herders would leave the farmers to clear the husked grains before releasing the cattle to graze.

But as Mikaila walked in the direction of the herders to complain about the disturbance, several arrows rained down on him. When the herders ran out of arrows, Mikaila says that one of them charged at him with a machete.

“I was carrying a bunch of wood for the workers. The herder cut up the wood and then my hand,” he says, gesticulating with his unhurt arm. “Now they say the hand cannot be a hand again. It has to be amputated.”

A younger victim who came to Mikaila’s aid was struck on the head. He had major nerve damage and had to be transferred to a better-equipped health facility in a neighboring state.

A new wave of bloodshed

Mikaila has been farming for over 40 years, but this is the first time an encounter with herders has been life-threatening. “We have issues from time to time, but it has never escalated to violence,” he notes. The Dec. 15, 2021, incident that harmed Mikaila and another farmer is just one in a larger pattern of growing hostilities between herders and farmers in this region.

At least 3,641 lives were lost to the crisis between 2016 and 2018, according to Amnesty International, with over half of the fatalities recorded in 2018 alone. In the first half of the same year, an estimated 300,000 people were displaced for the same reason. The north-central region of Nigeria has notably been the hotbed of these clashes. But the violence is fast spreading to other parts of the country, including the south.

Decades ago, farmers and herders in Nigeria enjoyed a relatively peaceful coexistence. In the pre-colonial era, mechanisms such as the traditional administrative system which regulated grazing activities and demarcated cattle migratory routes, known as the burti, were key to establishing clear boundaries between farmers and herders. In recent years, however, these mechanisms have started to collapse.

Conflicts involving pastoralists as perpetrators and victims in Nigeria from Feb. 2019 to Feb. 2022

The problem has only been exacerbated by banditry and the Boko Haram insurgency in the north, which has forced the nomadic Fulani herder households to migrate south. Thanks to improvements in veterinary medicine and cattle breeds, their herds can now survive tropical diseases in southern Nigeria.

But even if insecurity issues in the north were swiftly solved, the area would still not be attractive to return to. Climate change and human activity are driving desertification, a form of land degradation which leads to vegetation loss and fewer water sources.

And while the resources herders and farmers compete over – fertile land and water – are rapidly dwindling, the populations of both groups are fast growing. The result? Distrust. Attacks. Counterattacks. Even more distrust. And then a seemingly unending cycle of brutality and bloodbath.

In the last few years, the Nigerian government has begun to acknowledge the severity of the problem and allocated some resources to address it, but there have been a series of issues with the appropriation, delivery and, ultimately, effectiveness of these resources. The government has even tried to retrain some herders to work as ranchers, but there is little known about the progress of this initiative.

The end result of these controversial and often unsuccessful initiatives, when paired with the accelerating rate of desertification, is not just continued violence, but the potential elimination of entire ways of life with all but uncertain prospects for the future.

Escaping a gluttonous desert into bloodshed

In Zakkari, a town about 20 km south of Nigeria’s border with Niger, Muhammad Zakkari, 37, a local herder, stands on a lone uprooted tree, staring at the cloudless blue sky. Desert sands spread out in every direction, as far as the eye can see.

About 50 years ago, this town, part of Yusufari in Yobe state, was like any other community in Nigeria’s northeast. It had decent vegetation, a smooth road network, sun-baked mud buildings and people who had lived there for generations.

Today, besides one block of classrooms, a mosque, two wells, a dried out water trough for cattle, a borehole that hasn’t been pumped in months and a cluster of huts, one only sees miles and miles of sand dunes.

“Where you see these trees, there once stood people’s houses. But the desert has submerged this area,” says Zakkari, one of the town’s many displaced residents. “Over here was a cemetery, but now that is gone too. It used to be that the distance between us and [the desert] was so far, we couldn’t go there as kids. But now it has come right here,” he continues to flashback to his childhood. Zakkari points to a little pathway, barely navigable for cars and says, “There used to be a motorable road here, but not anymore.”

The Sahara, which is the world’s largest hot desert, grew 10% bigger between 1920 and 2013. According to one 2018 study, about two thirds of the expansion can be attributed to changes in natural climate cycles, while the remaining third is likely “due to human-driven shifts” in the region. Indeed, while climate variability and moisture losses on a global level are a major source of concern, human activities, such as deforestation, overgrazing, cropland expansion and unchecked population growth, are making an already worrisome situation even worse.

This has affected the semi-arid Sahel belt, which separates the Sahara from the fertile savanna ecosystem in the south. According to one estimate, the sand dunes encroach into Nigeria at the rate of 30 hectares every year, putting 11 out of the country’s 36 states at risk of desertification. In Yusufari, satellite analysis further shows that vegetation shrank by 91.7% between 1984 and 2021, while the area experienced a 71.9% decline in water resources in the same period.

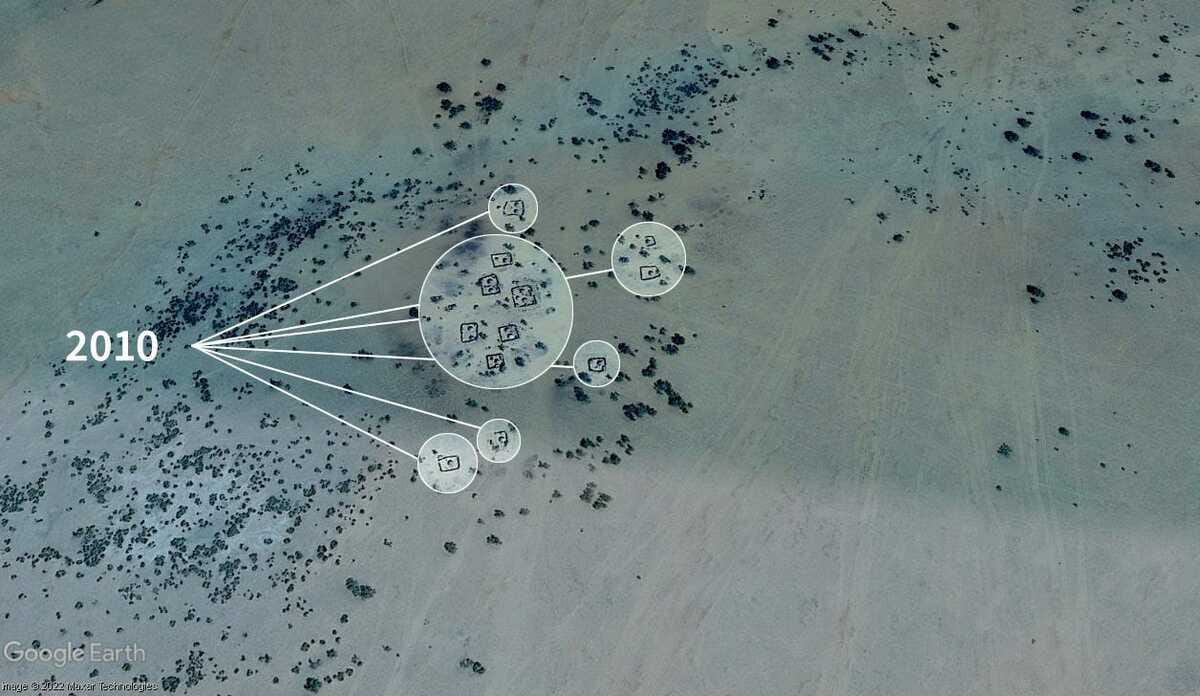

Land cover change in Yusufari from 1984 to 2021

Zakkari is one of the communities in the Sahel, but satellite data shows other villages in Yobe state, such as Faragaa, Gafade, Garshelek, Kilboa, Ndijiu, Njikilamma, Sadan and Sakaa, have suffered much worse fates. As the Sahara expands, the local herding communities are forced to move elsewhere to improve their chances of survival.

Further into the hinterlands of Yusufari, Bamalu, a 43-year-old herder who only provided his first name, tells a similar story. “More than 100 households have left. Some went north; some went south,” he says. A few like him are holding out. “We are suffering because of reduced rainfall. We want the government to help us. We grew up here. We will die here. But we have entered this situation, and we don’t know what to do.”

Moving, especially if one stays within the arid north, is not much of an improvement. Throughout Yusufari, thousands of livestock starve to death – especially during the later days of the dry season between March and May. By this time, edible grasses have died off, and they must rely on stored grasses, sorghum, millets, pines and chaff, which do not last long.

“If you look around, you will see dead animals, and it is all because of hunger,” notes Sulaiman Khalil Adam, secretary of the cattle breeders association in Yusufari. “We do not always have a successful rainy season. We only see rain just about eight times a year, and that is not enough.”

Disappearing communities in Yusufari

During the dry season, herders are forced to sell their emaciated cattle at incredibly low prices. Complicating matters, traders from across the border in Niger prefer to sell their cattle in Nigeria because of decreased regulation. The end result means lower prices for everyone.

So folks are moving as far south as they can. Seven years ago, Mallam Musa Mohammad, 45, a herder from Geidam, Yobe state, traveled over 400 km southwards to Song, an area in Adamawa state, and never looked back. He was escaping the security risk of Boko Haram and searching for water and grazing grass. Supported by branches of the Benue River, Song has a decent amount of both.

Mohammad migrated with two wives; 15 children and grandchildren; two brothers, Isa and Ahmad, who equally had large polygamous households; parents; and hundreds of cattle and sheep. Many of their kinsmen from Geidam have undertaken the trip too, resettling in places such as Gombi, Maiha and Mubi in Adamawa; Askira, Damboa, Jere and Konduga in Borno; as well as Gujba and Gulani in Yobe.

Though Mohammad says his people have not encountered problems with the locals, analysis of press reports documented by the Council on Foreign Relation’s Nigeria Security Tracker shows that at least 305 people were killed across Adamawa between 2016 and 2021 in herder-related clashes.

Dr. Kabir Adamu, a security expert who heads Beacon Consulting, says while there is still little research directly connecting climate change to increased conflict situations in Nigeria, it is clear that environmental factors play a decisive role in the crisis. And it is not a problem limited to the northeastern region.

“There’s virtually no part of the northwest, and to an extent the north-central region, where you will not see receding water bodies,” says Adamu. “The impact on the people’s socio-economic wellbeing and livelihoods is causing an increase in crime, as well as the possibility of migration from locations that are worst-hit to other places.”

A stark example of this is the Hadejia-Nguru wetlands, about 100 km west of Yusufari. For as long as residents can remember, the wetlands have sustained a life of peace and abundance, supporting farmers, herders, fishermen and waterbirds. The rice harvested in Nguru attracts merchants from far and wide, including states such as Bauchi, Jigawa, Kaduna and Kano. Even more famous is the fish business. Residents proudly describe the area as the headquarters of fishermen, who come from various places.

However, spatial analysis revealed that the wetlands, which stretched over an area of about 2,600 km² in 2000, had receded to about 1,800 km² by 2020. The shrinking, of course, limits crop yields.

Farmers recall their most recent poor rice harvests in 2021. “From a dozen bags of rice to ‘hopefully’ two,” Idris Abubakar says. “From a thousand bags to 10,” Adamu Isa says. One farmer even recalls that, in 2020, he gave 30 bags of rice to charity but was not able to harvest even 10 the following year.

As the wetland recedes, it also reduces the marshy buffer that keeps herders’ cattle away from farmlands, setting communities up for conflict. “I was hoping to get about 30 sacks, but here we are. The wicked lot! I couldn’t even get one sack. The cattle ate them all,” cries Inusa Lokasi, 57, one of many farmers in Tudun Gamboganari, Nguru.

While droughts have undoubtedly contributed to shrinking the wetland, so has human activity, especially the construction of dams along water routes supplying it, such as the Tiga Dam in Kano. Built in the early 1970s to boost agricultural activity, the Tiga Dam has caused significant economic losses in the Hadejia-Jama’are floodplain by changing the timing and size of flood flows, as well as by diverting surface and groundwater for irrigation.

Even the proliferation of the invasive Typha grass, introduced to Nigeria in the 1970s, is contributing to the issue. While people familiar with the plant, such as Native Americans, consider it edible and medicinal, in Nigeria it is a nuisance that blocks the waterways, as Madu Tandari, chairman of the association of farmers in Nguru, explains. It also germinates aggressively, grows up to three meters high and has the tendency to displace native species, reducing available farmlands and leading to the disappearance of pasture grasses necessary for herding.

A floundering government response

The Nigerian government has had the Typha grass problem in the Hadejia-Nguru wetlands on its radar for some time. In 2015, the environment ministry acknowledged that the plant was “causing flooding, loss of farmlands and conflict among farmers, herdsmen and fishermen.” At least twice between 2015 and 2017, former environment minister Amina Mohammed visited the wetlands in Yobe to study the situation.

And, in 2016, the government awarded contracts through the Presidential Initiative for the North East (PINE) to two companies, paying them ₦544 million ($1.3 million) to clear the invasive plant species, as well as to build water gates along the Yobe River. The contracts were, however, marred by corruption and are still the subject of a trial. According to federal lawmakers and the country’s anti-graft agency, former federal government secretary Babachir Lawal, who oversaw PINE, awarded funding to companies in which he had personal interests.

At the time, Lawal told reporters the allegations were attempts to malign him. While admitting he owned one of the contracted companies, he said he stepped down as its chairman before accepting his political appointment. Efforts to reach Lawal for additional comment, including by placing several phone calls to his former senior aide, were unsuccessful.

Though a 2017 senate probe revealed that ₦530 million ($1.2 million) had already been spent on the Typha grass project, on the ground local leaders say little was actually done – in part thanks to Lawal.

“Most of us will never forgive Babachir because that [the uncut grass] is the cause of our present predicament,” laments an official of the Nguru local government, who was not authorized to speak on the record. He says the contracted company’s workers complained that their equipment needed repairs, stopped working and have not returned to the site since then. He pleads for “whatever organization, agency or ministry to come to our aid… so that we will continue to maintain our peace.”

On a call with the North East Development Commission (NEDC), which oversees former PINE projects, an official who refused to reveal their name and position, sought to distance the commission from the presidential initiative that preceded it and awarded that particular contract. They said it is now a completely different entity, and while it sustained some of its predecessor’s programs, others were dropped “maybe because of the controversies.” Though the official did not confirm the Typha project was among those dropped, it has stopped appearing in recent NEDC budget reports.

To curb the desertification of the greater northern region, in 2015, Nigeria set up an agency to implement its portion of the African Union’s Great Green Wall Project, which seeks to plant 8,000 km of trees across the Sahel. By 2019, the National Agency For Great Green Wall (NAGGW) had reportedly restored 12 million acres of degraded land. But residents of desertifying areas and experts believe the project, and other tree planting exercises, could do a lot better.

Pointing to a small cluster of trees and grasses, which he recalls were planted some two decades ago on the outskirts of Yusufari, herder Sulaiman Khalil Adam says much of the vegetation in the area has died. “We have a shortage of plants that will protect us from the desert area. If we had planted the plants that would prevent further desertification around the time this thing started, I swear we would have defeated it by now,” he explains.

Between 2016 and 2022, about ₦9.6 billion ($23.3 million) was allocated to NAGGW. Out of that, ₦7.8 billion ($18.8 million) was for capital projects. These have typically been undertakings in afforestation (planting forests where they did not previously exist), ecosystem restoration, promotion of alternative livelihoods and improving water access e.g. by constructing boreholes.

Curiously, however, in its 2021 budget, the agency proposed to spend 47% (₦1.26 billion) of its capital allocation on providing solar street lights in various communities. In the 2022 budget, ₦250 million ($601,091) was earmarked for solar street lighting and ₦50 million ($120,218) for the fencing of schools.

NAGGW spokesperson Pauline Sule argues that providing street lights and alternative energy sources are a crucial part of improving welfare in desert-prone communities that are disconnected from the national power grid. “You cannot just plant trees and leave them alone,” she explains, adding that they need to be given the tools to be self-sustaining.

Nasreen Al-Amin, a climate justice advocate and executive director of Surge Africa, a nonprofit which promotes climate resilient policies, acknowledges the need to include such “job creation and community development” activities in the Great Green Wall project. However, she also notes such projects “are capital intensive and can divert funding from critical areas.”

To Damilola Ojetunde, a data analyst at the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), such “non-relevant projects” should have been axed during the budget planning and defense stages – and their inclusion reflects Nigeria’s lax auditing processes.

In recent years, the NAGGW also proposed spending ₦358 million ($861,612) on projects in Edo, Niger, Ogun, Osun and Taraba states, which are not among the 11 frontline Sahel states covered in its legal mandate.

Sule says such projects, which include awareness campaigns around the threat of desertification, are necessary to reduce the rates of farmer-herder violence in those states. She also blames some of the budget allocation on an alarming trend of “constituency projects,” whereby Nigeria’s federal lawmakers seek to include development funding for their districts, even if their constituents should not be the primary beneficiaries.

Even where afforestation has been attempted, locals point to wastage. One traditional leader in Yusufari, who asked not to be named, said that the trees have not been germinating properly. “They do it annually,” he says. “But for over three years no tree has grown.”

The planting is often done during the dry season, when the conditions are not favorable – a decision that Sule says is often the result of budget delays. Additionally, many residents are not informed of the initiative, and so they do little to maintain the trees – leaving them to wither and die.

Besides, the locals have much more immediate problems. “When someone needs rice, but you offer him fertilizer, won’t he choose rice? Give him both rice and fertilizer because there’s indeed starvation,” says an elder leader, who feared giving his name. He thinks people should receive food and cash support, in addition to long-term capital investments.

Even the government is known to abandon its own investments. One borehole in Zakkari, for example, has not worked in over a year because fuel is not supplied to power the generator. The operator who used to bring petroleum simply stopped coming. “No monitoring, no evaluation. They won’t even come to check out what sort of work was done,” cries the elder. The government has thus far not responded to requests for comment.

To Adamu, the key lesson from the Great Green Wall Project is that it should be locally-run rather than centralized: “It is not the federal government that should implement such projects but the states. They are the ones that are feeling the impact of climate change.”

Go ranch!

Herding predates modern states like Nigeria, and traditional grazing routes are said to extend as far as North and Central Africa. Nonetheless, modern state bodies have tried to regulate them. In 1965, the Northern Regional House of Assembly passed a law mapping out grazing areas, allowing livestock to migrate from one grazing reserve to another without passing through residential areas and farmlands. In places like Adamawa and Yobe, the routes are demarcated using painted drums or cone-shaped cement blocks.

But even the modern state has not stuck to its own rules. Many parts of the routes have been sold or converted into farms and new residential and commercial developments. About one kilometer off the Nguru-Gashua-Damasak road in Yobe is one example that repeats across northern Nigeria: an extensive farm, fenced with cement blocks and wire mesh.

“This is where the route is supposed to be, but these people are building inside it,” says Madu Tandari, the farmers association chairman in Nguru, pointing to the demarcating drums inside the fenced farm. He adds that the owner of the farm, a local district head, has been warned against using the location but has so far refused to relocate his investment.

The Great Green Wall project seedlings and a solar-powered borehole are under construction at a 10-hectare orchard in the Kirikasama area of Jigawa. The project was commissioned by Nigeria’s National Agency for the Great Green Wall (NAGGW) and, despite the ongoing construction, is considered complete as of November 2021. Photo by Kunle Adebajo

Muhammadu Buhari, the federal president, recently approved the review of grazing reserves with the aim of protecting the old and creating new ones. But some say the encroachment of farms and other developments is an irreversible trend that not even Buhari can undo.

Adamu says that even if the grazing routes are restored, “the era of open grazing, in my honest opinion, is over. Yes, as a temporary measure to allow for a de-escalation of the current situation, there may be a need to allow some form of movement.” But, in the long term, he believes herders should be encouraged toward “some more sophisticated type of livestock rearing.”

This may even be quite beneficial to the herders, says Dr. Salisu Damagum, a lecturer at Modibbo Adama University. “Traveling for 10 to 15 km will make it [the cattle] lose weight. The little feed that it will graze on its way is wasted on walking, not on meat or milk production,” he explains. Damagum believes herders can change their approach if they are exposed to modern livestock rearing techniques that will boost their productivity.

Dr. Mukhtar Yahaya Magaji, department head of animal science and range management at the same university, agrees with this sentiment, but points out that the average nomadic herder barely has the means to buy pasture to feed his animals. He “cannot even afford to sell one of [his] cattle unless the animal is seriously sick.”

Magaji also says that the government has historically neglected cattle-rearers, particularly in comparison to farmers. “Most of the government programs are targeted toward crop cultivation… You have to make programs that are targeted toward livestock production in order to improve productivity,” he says.

According to many scholars, ranching, which involves raising herds on large farms rather than grazing them while roaming, leads to better meat and milk production, fewer disease outbreaks and less risk to life. In Nigeria, authorities believe the approach will reduce competition over resources between herders and farmers.

Elsewhere, however, ranching has been criticized as a contributor to climate change because forests are often cleared to make room for the cattle farms, and livestock is estimated to generate as much as 14.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Methane released from cattle burps and manure is a huge part of the problem, but better breeding and changes in diet have been found to help.

The Nigeria Incentive-Based Risk Sharing System for Agricultural Lending (NIRSAL), in 2017, flagged off a pilot feed-finishing project in Adamawa to expose herders to modern techniques and encourage ranching. Anne Ihugba, NIRSAL’s head of communications, could not give any updates on the project, saying it predates her appointment. No formal updates on it are publicly available.

As the government tests and abandons solutions, in the desert frontline states, people like Mikaila, the bare-chested old man at the Nguru government hospital, pay a heavy price. Still, even without part of his left arm, Mikaila cannot abandon his farm. “I have no choice,” he says. “I have nothing at all. Since I left school as a young child, I have done nothing but farming.”

This report is a collaboration between HumAngle Media and the Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism (CCIJ) and funded by CCIJ.