A drive to Mzuzu on the 116 km stretch from Mzimba via Chikangawa in 1998 and before would always be an indelible experience—kilometre after kilometre of undiluted verdant charm.

A panorama of gently undulating hills of forest lushly decorated the roadside beyond the reach of the human eye in Malawi’s northern highlands, just off the grandeur of Lake Malawi.

That was the Viphya Plantation in boastful—almost arrogant—glory, a man-made green belt whose history stretches back to the rule of the late Hastings Kamuzu Banda.

But all that is no more; what remains are stumps that jut out as sad amputees on an ecological battlefield, thanks to mismanagement, political manipulation, greed, and upended priorities.

Literally, the brazen rape of an innocent project that would have sustained thousands of jobs indirect and downstream industries and kept this part of Malawi awesomely beautiful.

It would have boosted Malawi’s eco-tourism facilities like lodges, spas, and resort villages—complete with modern roads, schools, health facilities, and shopping malls.

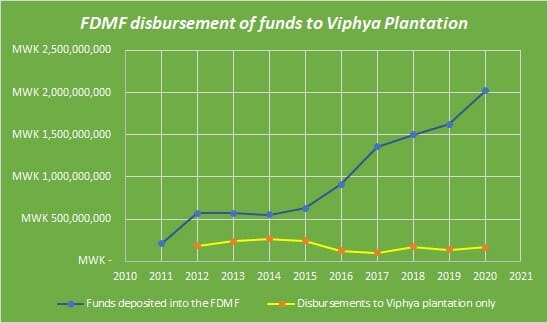

Of course, the plantation would be harvested one day, but not in the way it has been literally been razed down. Some MK1.7 billion that the government has sunk into the project in the last nine years seems to have suffered the same fate as the trees largely comprised of exotic pines.

Now, the authorities are dumping the buck merely on poor record-keeping at the plantation. “The Department of Forestry has noted poor record-keeping in the Viphya Plantation is working on improving this,” the Director of Forestry Clement Chilima said.

The tragedy, investigations have revealed, is explained by a whole array of other, avoidable, factors.

Since 1998, private companies and illegal lumberjacks have been hacking away at the Viphya Plantation.

The brazen involvement of politicians, especially those aligned to the ruling party from that time up to 2019, is to blame, to a large extent.

Former senior Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) ministers, Peter Mwanza and Goodall Gondwe were among the ‘vultures’ they circled on the Viphya project.

They reportedly went as far as facilitating a government-backed loan for the now-defunct Sterling Timber International, a politically connected company to secure MK1.4-billion from the now-defunct Malawi Savings Bank (MSB) in 2011 to set up a timber processing plant.

The factory, relying on the timber on the plantation, was never built and it remains unclear what the two politicians would actually benefit from the loan facilitation.

Sterling Timber secured the loan, which was guaranteed by another state institution, the Export Development Fund, from MSB despite having no experience in the timber business.

The Parliamentary Committee on Natural Resources and Climate Change has not delivered on the promise that it would “soon” name and shame politicians interfering with activities of the Department of Forestry in managing natural resources at Viphya Plantations.

The otherwise media-savvy Werani Chilenga, who is the committee chairperson, has ignored our questions on the matter, despite repeated reminders, but he acknowledges political manipulation in the Viphya project.

“There are a lot of politicians who are interfering with the management of our natural resources. And when we come to this plantation, we hear (that) this politician (is) doing this, another politician doing that…and these politicians are from all political parties. So we will produce the report, name and shame them and bring them to book,” Chilenga said some time back.

Compromised trade unions have also been circling on the plantation, using political links to gain from the project.

The Reformed Timber Millers Union (RTMU) invoked the political card in trying to persuade former President Peter Mutharika to increase its concession in the area from the current 4,000 hectares to 10,000.

A November 2017 letter to the ex-president that the Centre for Investigative Journalism Malawi (CIJM) is privy to indicates that the union approached Mutharika and promised him political support in exchange for a bigger stake in the plantation.

The letter reveals that RMTU claimed to have been supporting the DPP and BEAM—former First Lady Gertrude Mutharika’s charity.

It further pledged to keep surrendering royalties to the DPP and BEAM if he influenced the Department of Forestry to allocate them a bigger concession.

“We recently supported the BEAM project at Chisenga in Chitipa district. We contributed computers, cement, shovels, and other equipment for the project. The money was contributed by members of the Union and we will continue…,” reads the letter in part.

Wanton lugging has taken place since 1998 and promises to reforest have not brought any tangible results to the 53,000-hectare plot.

In 2012, the Malawi government claimed that replanting was taking place in the Viphya’s pine-based plantation, following a public outcry of aggressing logging. It claimed to replant 1600 hectares.

Paradoxically, official figures from the department of forestry show that an average of 815 hectares has been replanted yearly from 2012 to date.

A Forest Development Fund was created in 2012, managed by Malawi’s Forestry Department with a goal of collecting categories of payments, retaining 80% of revenue collected.

Revenue is collected from sales of trees, fuelwood, as well as rentals and permits issued to plantation operators – the loggers.

Despite the evident lack of progress on the ground, the Malawi government insists it is doing something to salvage the situation claiming the establishment of the Forest Development Fund will help in restoring the plantation to its glory days.

But nine years since the operationalization of the Fund, things seem to be worse than there were in 2012.

A mere 8,144.80ha that includes concession areas out of the 53,000 hectares has been reclaimed and it is estimated that, out of this hectarage, some 80 percent of the planted trees have survived, particularly in the areas that are under concession by private operators.

This means approximately 815 hectares are being replanted yearly and at this rate, it will take 55 years to restore the plantation to its yesteryears.

“Malawi requires a restoration movement and a “whole of government approach”—one that is led by farmers, communities, entrepreneurs, investors, NGOs and extension workers, and

government officials responsible for agriculture, forestry, finance, planning, and rural development among others,” said Patrick Matanda, Secretary for Natural Resources, Energy and Mining in the 2017 National Forest Landscape Restoration Strategy.

The Strategy outlines priority opportunities and interventions that can translate the potential of restoration into multiple benefits such as improved food security, better biodiversity, more reliable water supply, job creation, income generation carbon sequestration, and enhanced resilience to climate change.

Plantation History

The establishment of the Viphya Plantation started in 1949/50 with the planting of exotic softwood in a number of areas such as Luwawa, Chikangawa, Champhoyo, and Lusangazi with the initial aim of making the northern part of Malawi self-sufficient in construction timber.

The Malawi government planted most of the 53,000 hectares with pines, mainly P.patula, P.kesiya, and P.Elliottii.

However, at independence in 1964 Malawi’s first head of State, Dr. Hastings Kamuzu Banda decided that the country should invest in a pulp and paper industry to earn much-needed foreign currency.

This gave rise to the 53,000-hectare pine project in the South Viphya Forest Reserve that was managed by the State-owned Viphya Plywood and Allied Industries Corporation as an export-oriented venture that was probably the biggest man-made forest in Africa then.

The project was set up on the montane grasslands in the highlands.

Nevertheless, the government stopped the project in 1979 after a feasibility study indicated that the project would not be viable only to resume it in 1980 by planting more trees after commissioning another study that contradicted the initial one.

Unfortunately, the global recession and a reduction in export demand that year scared away investors, so the project was again discontinued, only to be resuscitated years later.

The strength of state control under Dr. Banda and foreign expertise kept the project intact and in good operational prowess, noted Dan Msowoya, a political analyst.

“For a long time, the forest project was managed by an expatriate. The project was self-sustaining and held out so much promise to the economic future of Malawi. The bad turn of events occasioned by the end of the contract of the expatriate management brought along with it the diametrically opposite profile of the project.

“It slowly degenerated into a liability, culminating in privatizing part of its operation. The succeeding governments of the multiparty democratic era exacerbated the already deteriorating management of the forest project,” Msowoya said.

Restoration, Income and Expenditure

Despite the huge problems that the project is suffering, the Malawi government is telling a tale of unbelievable success.

According to Vice President Doctor Saulos Chilima, the Viphya Plantation is generating MK4 billion revenue a year to the government and increasing timber exports.

“So far, about 70 percent of the 53,000 hectares of Viphya plantation is under private management, creating about 2,300 jobs,” the Vice President said after an interface meeting with Minister of Forestry and Natural Resources Nancy Tembo on the progress of reforms in the ministry in August last year.

There is little indication that reforestation is taking place but on paper there is tremendous progress as superfluously written documentation stashed at Malawi’s seat of government, the Capital Hill, claim.

Associate Professor Jarret Mhango of the Faculty of Environmental Sciences at Mzuzu University noted that the management of the Viphya Plantation is not taken as a priority but just like any activity in the line ministry.

“The main problems in the management of Viphya could be due to lack of a clear management strategy/policy for the plantation. If indeed a management plan is there, then there is no adherence to the plan.

“In forest management, every forest must have a management plan. If there is an overall management plan for Viphya then it is not being implemented,” Associate Professor Mhango said.

Political Analyst Dan Msowoya agreed with Mhango saying the government’s approach to the management of the Plantation is ‘Laissez Faire.

“Replanting has been haphazard and without the requisite care. Forest fires have become the order of the day because the fire prevention and control mechanisms and policies have since been abandoned and discarded” he said

At the 53,000 hectare Viphya Plantation, the Malawi government manages a paltry 9196 hectares.

The rest of the Plantation has been sliced as follows: 20,000 hectares for RAIPLY, Reformed Timber Millers Union (RTMU) 4000 hectares, AKL 6000 hectares, Kawandama 6000 hectares, Total Land Care 2500 hectares, Pyxus Agriculture 1998 hectares, Consolidated Processing Limited 1583 hectares, Greenwing Agriculture Resources 687 hectares, Kayola Constructions 584 hectares, Mbelwa Heritage Trust 500 hectares and Forest Services & Suppliers 448 hectares.

Now let’s do simple mathematics: Malawi's government has disturbed MK1,639, 396,019.75 into Viphya Plantation to manage 9196 hectares from 2012 to 2021. Roughly it means the government allocated MK 201,281 per hectare.

“These funds were largely used for replanting, tending operations e.g. weeding, conducting law enforcement, fire-fighting, payment to contractors and conducting maintenance work (vehicles, office buildings and water supply). The above figures are far below 80 percent of the Viphya’s contribution to the Fund per year,” the Director of Forestry, Clement Chilima said.

Most concessionaires are planting improved, certified seed. All costs associated with planting 1 hectare come to $1,000-$1,200. This includes: the cost of the imported seed; the nursing costs; the land preparation; the out planting; and fire prevention for 3 years, according to industry experts.

Msowoya feels that an everlasting solution to the plantation would be to place it under local government, with the two district administrations’ capacity being boosted through training and better resource allocation.

“Harvesting shall be regulated by these local government authorities in collaboration with a line Ministry, and a percentage of the proceeds shall be retained and maintained by the local government authorities to further maintain the forest,” he said.

Associate Professor Mhango insists, though, the government must prioritize the project and come up with a sustainable strategy.

“There must be an approved long term and short management plan for Viphya. The line ministry should create a department of plantations to manage plantations. We could devote a 3-4 year or national tree-planting programme to focus just on replanting Viphya,” Mhango suggested.

She blamed inadequate funding for the poor fortunes of Viphya and other plantations “But these (plantations) are unique and need a budget line of their own to manage them effectively,” Mhango said.

The mismanagement of the Viphya Plantation has dire long-term consequences if unchecked. Unprotected soil can also be carried away by the wind leaving the infertile lower soil layer exposed to the sun.

The exposed soil becomes an unproductive hardpan and develops desert-like features. The landscape may go through different stages and transform in appearance as the process of desertification takes place.

This story was first published on the Centre for Investigative Journalism Malawi (CIJM) – www.investigative-malawi.org.