In November every year, Zimbabwe’s second-largest city, Bulawayo, explodes into a magnificent riot of colour as the majestic purple jacaranda and the flame-red flamboyant trees bloom, transforming the wide tree-lined streets into a glorious spectacle.

But beneath this blissful veneer of blossoms is a troubled city struggling to come to terms with a devastating shortage of water and the resultant loss of life.

In June, three months into a Covid-19 lockdown, Bulawayo was blindsided by a totally different disease—diarrhea.

The gastro-intestinal malady, which spreads through the ingestion of contaminated water and food, had killed 13 people by July and infected more than 2 000 others. Some of the survivors suffered mysterious skin disfigurement. And many are yet to settle their hefty medical bills.

The Bulawayo Municipality said eight suburbs were affected. In September, city clinics were attending to more than 240 cases of diarrhea every two days. In comparison, Covid-19, at that time, had claimed six lives.

“The diarrhea outbreak caught many of us by surprise. We were bracing for a Covid-19 emergency, like everywhere else in the world. I can’t adequately describe the terrifying sense of fear and shock caused by the diarrhea outbreak under the shadow of the Covid-19 crisis,” recounted Mthokozisi Sibanda, a city resident.

The sprawling townships of Luveve and Cowdray Park was the epicentre of the diarrhea outbreak. Local residents recounted the ordeal of having to constantly dice with death, as the twin perils of Covid-19 and water-borne disease stalked the area.

The diarrhea-related deaths have since subsided, but emotional scars remain fresh, worsened by a water shortage that threatens to spiral out of control.

But even as that threat lessened, deaths in the city attributed to the coronavirus have increased in October and November. The increased toll from the virus comes amid warnings from Solwayo Ngwenya, a local professor of medicine and clinical director of Bulawayo’s largest hospital, that the reluctance of residents to wear face masks has increased the risk of a “second wave” of infections.

Climate change is real

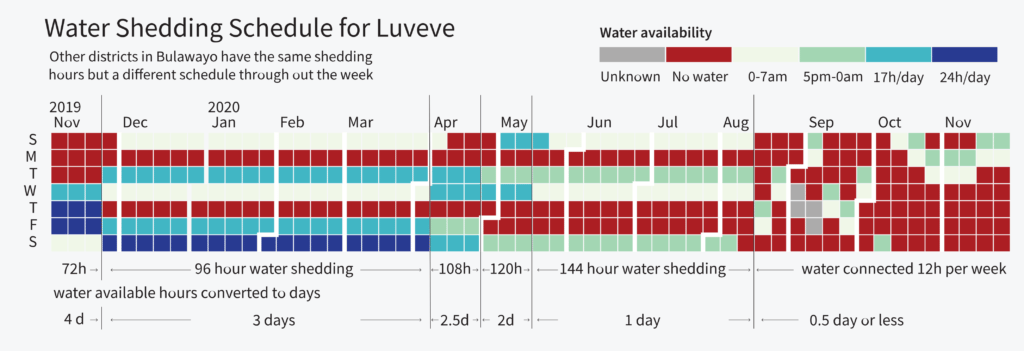

Three out of six water-supply dams have dried up owing to dwindling rain, forcing the municipality to introduce drastic rationing which has seen most suburbs receiving water for only 12 hours over an entire week.

The director of the Bulawayo City Council’s department of engineering services, Simela Dube, made the chilling revelation that Criterion Water Works, a giant reservoir holding 10 days’ buffer storage, has now completely dried up.

“It’s the first time in history,” Dube said. “The issues of climate change are starting to show. The inflows into our dams continue to decline almost every season.”

The city’s 650 000 residents need at least 150 megalitres (150 million litres) of water a day, but the municipality can supply only 89 megalitres, using five bowsers – tankers – for transporting water.

The huge disparity between supply and demand means people are forced to resort to unsafe sources of water, such as unprotected wells, contaminated streams and boreholes whose water quality is questionable.

Bulawayo City Council (BCC) says laboratory tests have ruled out fears that the diarrhea is caused by serious notifiable diseases such as cholera, typhoid and dysentery. Municipal health officials attribute the outbreak to residents’ poor hygiene practices, particularly the use of dirty water-storage containers.

Civic groupings have challenged this narrative, accusing the city council of supplying “tainted” water.

In the face of the mounting crisis, the municipality has sought permission from the central government to conduct a study to establish whether it would be feasible to allocate each household the first 5 000 litres of water for free every month, according to Dube. It is an ambitious “pro-poor” plan.

He says the study—which will also look into the viability of the water-tariff structure—will cost US$600 000.

“The study will also look into the ring-fencing of the water services so that water can account for its own expenditure and income without getting subsidies from other (municipal) accounts.”

Finding clean water is tough

Mother-of-two Anna Nduna, 21, said it has become very difficult to juggle the tasks of tending to her three-month-old twins while also frantically hunting for water.

“I am staying in Cowdray Park and the water situation there is very dire. Sometimes we spend three weeks without (municipal) water. Due to that, we ended up resorting to fetching water from unprotected wells near the [spilled] sewage,” she said.

“To make matters worse, I have three-month-old twins. So, I struggle to get water for washing their nappies and for cooking. I come here (looking for water) every day, two or three times a day. Today, I have been here since 1pm and now it’s already 4pm,” she said while attending to her crying babies.

The distance between her home in Cowdray Park and where she fetches water is about a kilometre.

Asked how she manages to carry a 20-litre bucket of water plus her twin babies, she said: “I strap one of my babies to my back and the other one in front. There is nothing I can do. The situation is horrible and unbearable.”

Her husband works as an illegal artisanal gold miner in Inyathi, 68 kilometres from Bulawayo and the family’s modest income does not afford her the luxury of buying borehole water from private suppliers.

Tormented by a running stomach

Sikhathele Ncube, 43, a mother-of-three and resident of New Luveve township, said diarrhea is terrorising her family.

The water situation in Luveve is unbearable for residents, made worse by a burst pipe that was spewing untreated effluent close to where many residents collect water when I visited the area.

“We fetch water near the sewage because we don’t have options,” Ncube said, referring to a nearby broken pipe that was spewing raw effluent when I visited the area.

“We wake up at 2am to queue for water at the wells here,” said Ncube. “I use this water for cooking, drinking and washing. Just look at that,” she gestured, pointing at a nearby pile of human waste.

“People are sick with diarrhea and other water-borne diseases. As I speak, I have a running tummy, and so do my children. We don’t care whether the water is safe or not,” she said.

It takes her an agonising 40 minutes to fill up a 20-litre bucket.

Read the rest of the story here.

This investigation was developed with the support of Wits University.